Name: Yuan Dynasty Blue and White Mei Ping with Dragon Motif

Dynasty: Yuan

Dimensions:

Outer Rim Diameter: 5.4 cm

Inner Rim Diameter: 3.2 cm

Height: 44.6 cm

Base Diameter: 14 cm

Description:

This vase features a small mouth, full shoulders, slanting belly, constricted lower body, flat base, and a circular foot. The form is grand yet elegant, with smooth and graceful lines. The body is thick and dense, glazed both inside and out with a transparent glaze that is subtly bluish-white in tone. The outer surface is decorated in underglaze blue: lotus petal and scrolling floral motifs adorn the shoulder, while a cloud-and-dragon design embellishes the belly. The dragon’s head is proudly raised, its mane flowing and eyes wide open with vigor. Each claw has four sharp, curved talons shaped like crescent blades. The dragon’s body is strong and sinuous—its head visible while the tail disappears from view. Around the foot runs an upward-facing lotus pattern.

The composition is rich and layered, intricate yet harmonious. The blue pigment is vivid and brilliant, with areas of dark brown “iron spots,” typical of the Sumaliqing (Persian cobalt) used in Yuan blue-and-white porcelain. The unglazed base reveals clear spiral traces from the potter’s wheel.

Unlike civilian kiln wares, the dragon motif was reserved for the imperial family, marking this piece as a tribute porcelain of royal use. The vessel form is that of a meiping (plum vase), which first appeared in the Tang dynasty, took shape in the Song, and was named in the Qing. It has been praised as “the finest vase under heaven.” Originally used as a wine vessel, the meiping—slender and refined—was known in the Song as a “jingping” and later, from the Ming dynasty onward, as a “plum vase.” The plum blossom, which blooms first among flowers and endures the harsh winter, symbolizes integrity and resilience. Naming the vessel after the plum elevated it from a utilitarian wine jar to an object of artistic appreciation and poetic sentiment, embodying the spirit of “Only after enduring the bitter cold does the plum blossom release its fragrance.”

This particular vase was once part of Emperor Qianlong’s collection. The emperor commissioned the court painter Giuseppe Castiglione (Shining Lang) to create a painting of it. Both the vase and the painting were preserved together in a specially crafted golden nanmu (Phoebe zhennan) box, as part of The Old Summer Palace (Yuan Ming Yuan) imperial collection.

Historical Context:

During the Yuan Dynasty, China was unified under a powerful military regime that consolidated the north and south, opened connections across Central and Western Asia to Europe, introduced foreign cultural influences, and revitalized both overland and maritime trade. Within this political and social landscape, the imperial government also reorganized and centralized the national porcelain industry.

In 1278 (the 15th year of Zhiyuan, under Emperor Kublai Khan), an imperial decree established the Fuliang Porcelain Bureau in Jingdezhen, tasked with producing ceramics for official use, court rituals, and government-supervised trade. This was intended to meet both the needs of the imperial household and the demands of international commerce. Following national unification, large numbers of craftsmen were relocated to Jingdezhen under state mandate through the “artisan registration system (jiangji zhi)”. At its height, the town housed over 90,000 artisans from all over China, giving rise to the saying: “Craftsmen come from all directions, and their wares travel across the world.” This marked the beginning of Jingdezhen’s rise as China’s enduring porcelain capital, a position it maintained for centuries. The Yuan era played a decisive role in advancing blue-and-white porcelain, improving its production techniques, enhancing cultural exchange, and expanding its trade reach.

As the first unified dynasty established by a non-Han ethnic group, the Yuan also brought distinctive cultural and spiritual influences to its art. The deep blue and pure white tones of Yuan blue-and-white porcelain reflect the Mongol aesthetic ideals of “reverence for white and blue.” This taste was closely tied to their totemic beliefs. According to The Secret History of the Mongols, “Genghis Khan’s forefather was born from the union of the blue-gray wolf, Borte Chino, and the pale white deer, Qo’ai Maral, who had a son named Batachikan.” The legend of the Blue Wolf and White Deer, passed down through generations, made the wolf a sacred totem of the Mongol people. The colors blue (cang, meaning azure) and white thus became symbols of purity and divine favor, deeply ingrained in Mongol culture. This cultural affinity explains the Yuan rulers’ particular fondness for blue-and-white porcelain—where vivid cobalt blue motifs roam freely across a pure white glaze, embodying both imperial grandeur and ancestral symbolism.

The vast empire and multicultural environment of the Yuan period further fostered artistic innovation. Persian ceramic techniques and aesthetics flowed into China, merging with Jingdezhen’s increasingly sophisticated craftsmanship. The resulting blue-and-white porcelain combined imperial elegance with exotic charm, earning admiration from the Yuan royal family, nobility, and even foreign elites. Meanwhile, new decorative innovations such as underglaze red (youlihong) emerged, ushering in a transition from plain monochrome wares to richly colored ceramics. This era marked a turning point: Jingdezhen, enriched by global exchange and superb artisanship, rose above all other kilns to become the unrivaled “Porcelain Capital of the World.”

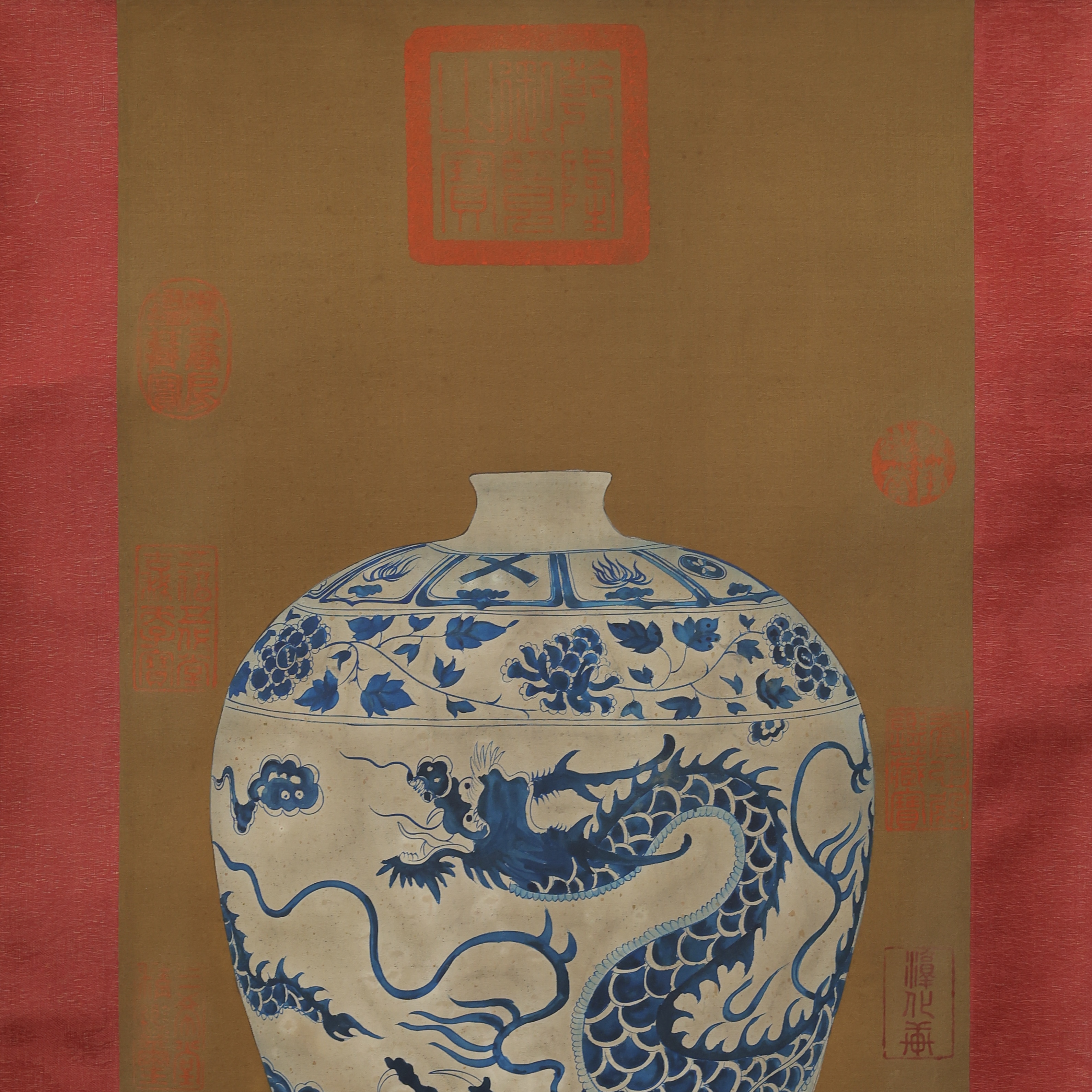

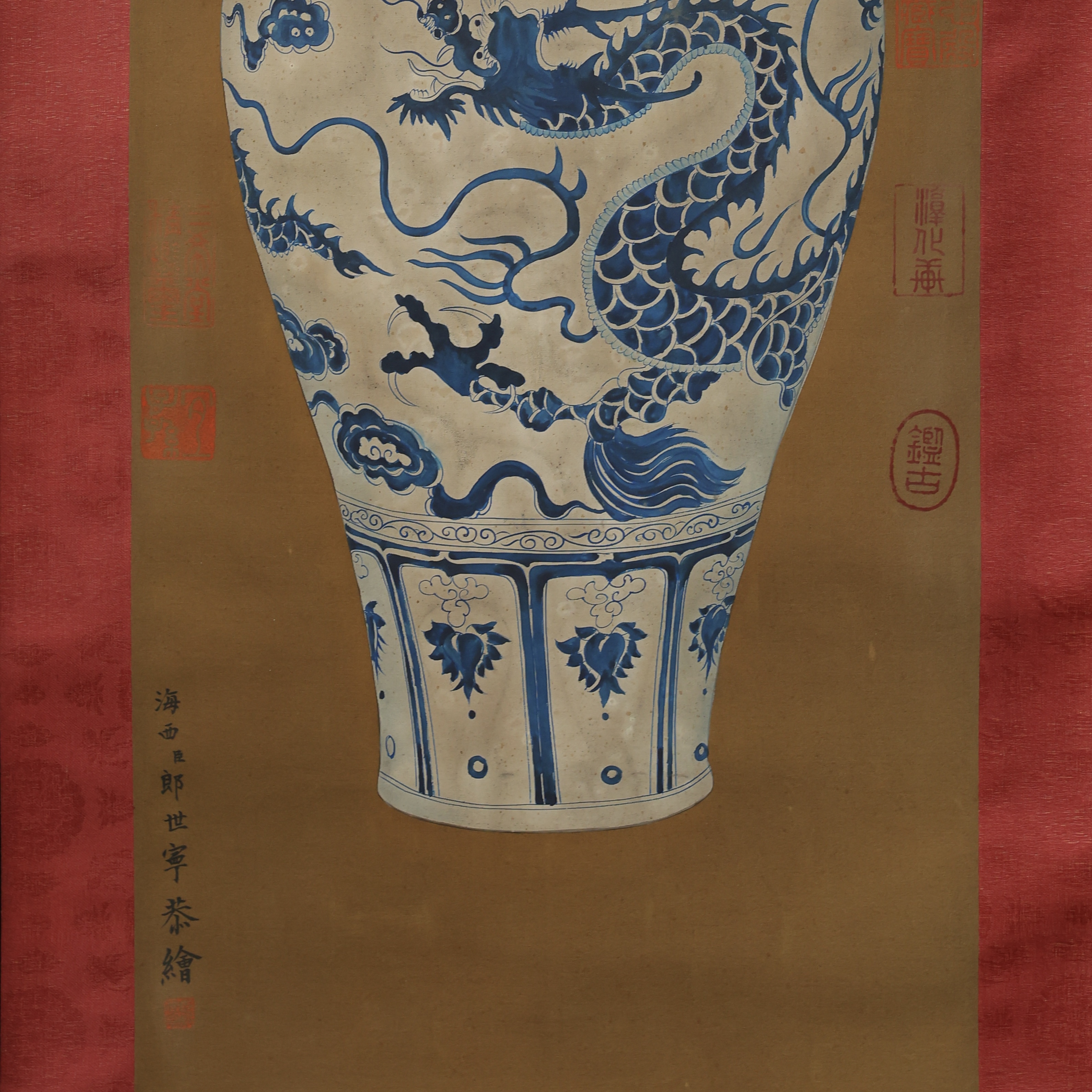

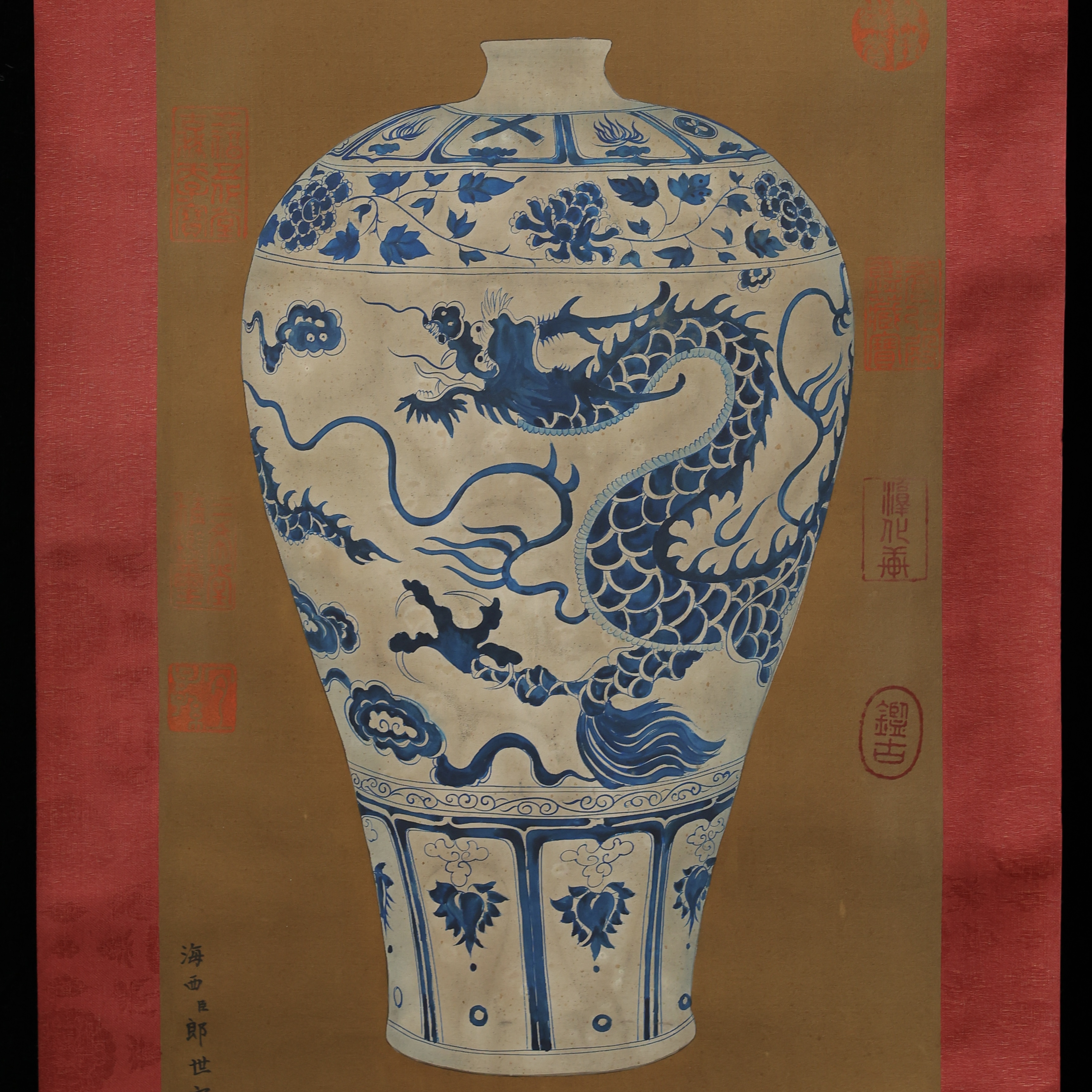

Title: Porcelain Treasure Scroll — Painted by Lang Shining (Giuseppe Castiglione), Qing Dynasty

Dynasty: Qing

Dimensions:

Painting Core: 27 cm × 61.6 cm

Scroll: 92.4 cm × 36 cm

Material: Silk

Artist: Lang Shining (Giuseppe Castiglione)

Inscription: “Respectfully painted by Lang Shining,servant of Hai Xi” (海西臣郎世宁恭绘)

Seals:

Seal of the servant Lang Shining (臣郎世宁)

Collector’s Seals:

- Treasure inspected by Emperor Qianlong (乾隆御览之宝)

- Collection of the Yangxin Hall (养心殿鉴藏宝)

- Appreciation of Antiquities (鑑古)

- Seal of the Studio of Three Rarities (三希堂精鉴玺)

- Collection of the Imperial Study (御书房鉴藏宝)

- Treasure of the Hall of Five Blessings and Longevity of the Rare Emperor (五福五代堂古稀天子宝)

- Auspicious for Descendants (宜子孙)

- Chunhua Studio (淳化轩)

Description:

This painting centers on a Yuan blue-and-white Mei Ping with dragon motif, executed with a harmonious blend of meticulous gongbi (fine-line brushwork) and Western realist techniques. The composition is elegant and direct, with smooth, precise outlines typical of Chinese court painting. The blue-and-white coloration of the porcelain, along with the intricate dragon and floral designs, are faithfully rendered in the artwork.

Through the introduction of Western perspective and chiaroscuro, Lang Shining imbued the vase with a tangible sense of volume, light, and ceramic texture, creating a lifelike representation that transcends mere depiction. This artistic synthesis vividly reflects Emperor Qianlong’s admiration and reverence for the Yuan blue-and-white vase, which was treasured within the imperial collection and celebrated as an object of both cultural and aesthetic significance.

Title: “Yuanmingyuan Imperial Collection” Box

Dynasty: Qing

Dimensions:

Length: 55 cm

Width: 47.4 cm

Height: 41 cm

Material: Golden Phoebe zhennan (Gold-thread Nanmu)

Description:

This exquisite box is crafted from gold-thread nanmu, with gilded exterior decorations and assembled using traditional mortise-and-tenon joinery. The structure is ingeniously designed—stable, tightly fitted, and masterfully executed. The top and front panels are intricately carved with a pair of dragons, facing each other with open jaws and powerful claws amid swirling auspicious clouds. Between them, the inscription “圆明园珍藏” (“Treasures of the Yuanmingyuan”) is engraved in bold kaishu (regular script). The surface exhibits a rich, lustrous patina developed over time.

Each side of the box bears a metal handle ring, and the front is secured with a metal lock clasp. The interior is lined with golden brocade silk, embroidered in blue, red, and black silk threads depicting ruyi cloud motifs and sea-wave patterns—an elegant and luxurious finish befitting imperial craftsmanship.

In Chinese history, nanmu (Phoebe zhennan)—also known in ancient times as nan, jiaorang wood, or cooperative wood—has long been revered. Historical texts such as Notes on Strange Things (Liang Dynasty) record:

“On Mount Huangjin grows the nan tree: one year its eastern side flourishes while the western withers, and the next year the reverse occurs—hence it is called the cooperative tree.”

Other classical references, including works by Lu Zhaolin and Wang Xiangjin, describe its noble growth, elegant form, and symbolic “mutual yielding” nature. By the Eastern Jin period, Guo Pu’s commentary on the Classic of Mountains and Seas identified the character “楠” and its pronunciation as “nan.” Later texts, such as Tao Hongjing’s Supplementary Records, even note its medicinal value.

Throughout history, nanmu, camphor, zelkova, and beech were regarded as the “Four Great Timbers” of China—with nanmu ranked first. The Compendium of Essential Knowledge further classifies it into three varieties:

1. Fragrant Nanmu (xiangnan) – violet-tinted, delicately fragrant, with beautiful grain.

2. Water Nanmu (shuinan) – softer in texture.

3. Gold-thread Nanmu (zhen nan or jinsinan) – featuring brilliant, shimmering fibers resembling golden threads.

Among them, gold-thread nanmu is the most prized, famed for its radiant luster, warm texture, and gem-like beauty that endures and deepens with time. Ancient connoisseurs described it as “wood with the grace of gold and jade—divine material shaped by nature.”

In imperial China, gold-thread nanmu was considered the most precious and superior building material. It was widely used in constructing palaces, temples, and imperial tombs, reserved exclusively for royal use. Prior to the Daoguang period of the Qing dynasty, its felling and allocation were strictly monopolized by the court, managed through dedicated imperial offices—hence it was also known as “emperor’s wood.”

Renowned for its exceptional resistance to decay and pests, ancient texts praised it with the saying:

“Water cannot soak it; ants cannot bore through it.”

Today, gold-thread nanmu grows mainly in Sichuan, Guizhou, Hubei, and Hunan, thriving in humid subtropical valleys at altitudes between 1,000–1,500 meters. It takes 60–90 years to mature, and over a century to become structural-grade timber. By the mid-Ming dynasty, mature gold-thread nanmu had already become exceedingly rare—making artifacts like this imperial Yuanmingyuan collection box an invaluable relic of China’s artistic and material heritage.

Related Figures:

Yuan Huizong Toghon Temür (1320–1370), also known as Toghon Temür, was the 11th emperor of the Yuan dynasty and the 15th Great Khan of the Mongol Empire. He was the last emperor to rule a unified China under the Yuan dynasty, the eldest son of Yuan Mingzong and Shidezhang, and the elder brother of Yuan Ningzong Yilin Zhiban.

Emperor Qianlong (Aisin Gioro Hongli, 1711–1799) was the sixth emperor of the Qing dynasty, also known by his courtesy names Changchun Jushi and Xintian Zhuren, and in later life as the Old Emperor of Ten Perfections. His reign title “Qianlong” means “the heavenly way flourishes.” He ruled for sixty years, and after abdicating, continued to exercise supreme power for another three years of regency, effectively maintaining control for a total of sixty-three years and four months, making him the longest-reigning and longest-lived emperor in Chinese history.

Giuseppe Castiglione (Lang Shining, 1688–1766) was a Jesuit missionary and painter from Milan, Italy. He arrived in China in 1715 (the 54th year of Kangxi) to preach and soon entered the imperial court as a court painter. Serving under the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors, he spent over fifty years creating art in China and participated in designing the Western-style buildings of the Yuanmingyuan (Old Summer Palace), becoming one of the top ten court painters of the Qing dynasty.

Lang Shining excelled in painting horses, portraits, flowers, and animals, blending Western painting techniques with traditional Chinese brushwork. His work was highly favored by the emperor and had a profound influence on Qing court painting and aesthetic tastes after the Kangxi period. His major works include Ten Fine Horses, Hundred Horses, Qianlong Grand Review, Auspicious Harvest, Flower and Bird Paintings, Hundred Sons, Gathering Auspiciousness, Immortal Hibiscus in Eternal Spring Album, and Heart-Mind Depiction of a Peaceful Reign (including the Scroll of Qianlong’s Consorts).